A TOWERING MASTERPIECE COMES TO CONNECTICUT

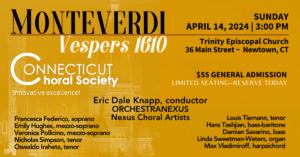

MONTEVERDI VESPERS 1610

Sunday, April 14, 2024 – 3 pm

TRINITY EPISCOPAL CHURCH 36 Main Street, Newtown, CT

General Admission is $55 with limited seating!

Tickets may be purchased online or at the door. Purchase Tickets Online Today!

The Connecticut Choral Society proudly invites you to a special presentation of “one of the greatest works of sacred music ever written” – the MONTEVERDI VESPERS 1610. We will perform together with the internationally acclaimed ORCHESTRANEXUS, Nexus Choral Artists, and renowned soloists Linda Sweetman-Waters, organ and Max Vladimiroff, harpsichord under the direction of Maestro Eric Dale Knapp.

This masterwork of the early Baroque period is an extraordinary and revolutionary setting of the five psalms, hymn, and Magnificat which make up the Vespers liturgy. The MONTEVERDIVESPERS 1610 is a grand scale production with multiple choirs, soloists, harpsichord, organ and orchestra featuring majestic choruses, poignant duets, and virtuosic solos of breathtaking beauty. It is seldom performed live in its entirety.

Don’t miss this rare opportunity to experience the unforgettable masterpiece that has inspired composers, performers, and audiences for over four centuries. Reserve your seats now as space is limited by clicking below to purchase tickets now or scanning the QR code. For more information or to learn more about how you can support The Connecticut Choral Society, please visit us at www.ctchoralsociety.com or Like/Follow us on Facebook and Instagram @connecticutchoralsociety.

ABOUT THE PROGRAM

We will be singing the MONTEVERDI VESPERS 1610, led by Maestro Eric Dale Knapp and accompanied by Linda Sweetman-Waters, organ and Max Vladimiroff, harpsichord.

MUSICAL ARTISTS AND SOLOISTS

ORCHESTRANEXUS

Nexus Choral Artists

Francesca Federico, soprano www.francescafederico.com

Emily Hughes, mezzo-soprano www.emily-hughes.com

Veronica Pollicino, mezzo-soprano www.veronicapollicino.com

Nicholas Simpson, tenor www.nicholassimpsontenor.com

Oswaldo Iraheta, tenor www.oswaldoiraheta.com

Louis Tiemann, tenor www.louistiemanntenor.com

Hans Tashjian, bass-baritone www.hanstashjian.com

Damian Savarino, bass www.damiansavarino.com

VESPERS 1610

Soloists: 1 soprano and 2 mezzo-sopranos

Instruments in sources: 2 recorder, 3 cornetti, 3 trombones, 2 violins, 3 violas, bass violin (or cello),

contrabasso da gamba (violone), organ (also often used in continuo: harpsichord, theorbo, dulcian)

I. Deus in adjutorium/Domine ad adjuvandum

II. Psalm 109: Dixit Dominus

III. Motet: Nigra sum

IV. Psalm 112: Laudate pueri

V. Motet: Pulchra es

Vi. Psalm 121: Laetatus sum

VII. Motet: Duo Seraphim

VIII. Psalm 126: Nisi Dominus

IX. Motet: Audi coelum

X. Psalm 147: Lauda Jerusalem

XI. Sonata sopra “Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis”

XII. Hymn: Ave maris stella

XIII. Magnificat

- Magnificat anima mea

- Et exultavit

- Quia respexit

- Qui fecit mihi magna

- Et misericordia

- Fecit potentiam

- Deposuit potentes de sede

- Esurientes implevit bonis

- Suscepit Israel

- Sicut locutus est

- Gloria Patri

- Sicut erat in principio

ABOUT MONTEVERDI’S VESPERS 1610

Monteverdi’s Vespers are an extraordinary and revolutionary setting of the five psalms, hymn, and Magnificat which make up the Vespers liturgy. In addition to these standard movements, Monteverdi included four motets (sometimes called “concertos”) for one, two, three, and six voices respectively, based primarily on love poetry from the Song of Solomon. There is also an instrumental sonata movement over which is woven the chant “Sancta Maria dona pro nobis.”

We take the cue for our performance from the setting of Sant’Andrea church in Mantua on that spring day in 1608: the grand opening of festivities for an extraordinary royal wedding. The excitement of the cantor is palpable as he intones the chant that sets the drama in motion: Deus in adjutorium meum intende. “God, make speed to save me” – the ordinary words of the Vespers, but not so ordinary today. The company of musicians responds with electrifying joy, launching the fanfare, the pageantry, and the royal procession of the Gonzaga family and the House of Savoy.

Even today, in an age which has heard Bach’s Mass in B minor, Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, and the requiems of Berlioz and Verdi, the Monteverdi Vespers of 1610 is astonishing for the grandeur of its conception and the opulence of its sound. For its time, it was unprecedented. No other surviving work from that time is written on such a scale, combining the grandest of public music with the most intimate of solo songs; no other such work calls for the many colorful obbligato instruments and uses them in such a daringly modern, virtuosic way.

Like the music itself, the performing forces required by the Vespers are on a grand scale. Monteverdi calls for seven solo singers. The chorus must be large enough to divide into anywhere from four to ten voice parts, and it sometimes divides into separate choirs. The orchestra displays a rich variety of instrumental colors, including virtuosic solo parts for violins and cornetti, but the instruments are specified only in certain movements. For much of the piece, it is the conductor who must determine the orchestration – whether to double voice parts with instruments and, if so, where to do it, as well as which instruments to use in the many parts of the music where they are not specified. It is also left to the conductor to decide whether to assign some passages in the choral movements to solo singers. Thus the Vespers can vary greatly from one performance to another.

The orchestra for this early Baroque work is still essentially a large Renaissance ensemble. While a later orchestra would normally be built around a central core of the string section and add various solo winds, Monteverdi’s orchestra consists of three more or less equal sections. There is the string section, comprising violins, violas, cellos, and violone, the last being the double bass of the gamba family, an instrument with six strings and frets.

Second, there are the winds. These include three cornettos, curved wooden instruments with about the same range as the trumpet; they are virtuosic instruments like the violins, and in this work occasionally have to play in their extreme high range. The winds also include three sackbuts (early trombones), Renaissance recorders, and, in our performance, a dulcian (early bassoon). Finally there is the continuo section, which is responsible for playing the bass line and improvising the harmonic accompaniment. For this, our performance uses an organ, a harpsichord, two lutes (one of them the larger theorbo), and a cello.

When the Vespers first appeared in print (Venice, 1610), Monteverdi was still employed at the ducal court in Mantua. No one knows whether it was actually performed in Mantua or written with an eye toward employment elsewhere – Venice or perhaps even Rome (the publication was dedicated to Pope Paul V). In any case, it must certainly have served Monteverdi well when he applied for and won the prestigious post of maestro di cappella at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice in August 1613.

By Monteverdi’s time, the Catholic Church had developed a strong cult of the Virgin Mary, and a good deal of music was dedicated to her. There were a number of special Marian feasts during the course of the year, and Monteverdi’s music sets texts that all of these feasts have in common. In addition, the Vespers includes a sonata, as well as non-liturgical motets, which Monteverdi interpolates between the psalms. The music could therefore be used for various Marian feasts during the year.

In order to make a complete Vesper service, added to Monteverdi’s music would have been the parts of the liturgy that change from one feast to another – the chants appropriate for that day – before each of the psalms and the Magnificat. We follow that practice in this performance, using chants for the Feast of the Assumption (August 15). There are two reasons for choosing chants for this particular feast. For one, a major Marian feast, such as this one, might be an appropriate occasion to employ a large ensemble, such as the one Monteverdi requires here. In addition, the Feast of the Assumption occurs at the time of year when Monteverdi was auditioning for his post at St. Mark’s, and he almost certainly would have performed the work at that time.

One of the most glorious and moving features of this Vespers is found in the way Monteverdi has chosen to unify it. Like Bach, who draws inspiration from the restrictions of writing in the most complex counterpoint, Monteverdi undertook the forbidding task of building all his major movements – all the psalms, the sonata, the hymn, and the entire Magnificat – upon the traditional Gregorian chants for those texts. In other words, he used the notes of the old chant as a fixed voice (cantus firmus) upon which to build elaborate compositions. This is easiest to hear in the closing Magnificat, where, in one short movement after another, the chant is sung in long notes, while solo singers and instruments perform faster notes around it. This creates a clash of styles – an astonishing variety of “modern” music superimposed upon an old-style technique. The two styles are reconciled with breathtaking beauty, and the technique allows Monteverdi to build an enormous structure that goes beyond anything his contemporaries were able to achieve.

Here are a few details that might be useful while listening:

-

- The “Nigra sum” (the only solo song in the Vespers) and “Pulchra es” are settings of sensual poetry from the Song of Solomon, poetry which had long been associated allegorically with Mary.

-

- In “Duo seraphim,” two angels, sung by two tenors, are calling to each other across vast space. When the text turns to the Trinity, a third tenor joins them; and at the words, “these three are one,” the three voices come together on a single note.

-

- The “Audi coelum” features a wonderful word-play: from a distance, one tenor echoes the phrase endings of the other, and as he echoes only a part of the last word, he forms a new word as an answer to the first tenor.

-

- The Sonata sopra Sancta Maria is the only real instrumental piece in the whole Vespers. As the virtuosic instrumental music unfolds, the sopranos of the chorus repeat a phrase of chant eleven times over constantly varying music.

ABOUT CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI

Born: 1567, Cremona

Died: 1643, Venice

“Rest assured that, as far as consonances and dissonances are concerned, there is another point of view to be considered besides the already existing one, and that this other point of view is justified by the satisfaction it gives both to the ear and to the intelligence.”

Monteverdi was a pivotal composer in the transition from Renaissance to Baroque styles in music. He was precocious – publishing his first book of sacred music when he was 15 – and prolific in almost every genre of contemporary vocal music, from madrigals to opera. His reputation as a radical was well earned, but he was concerned to be acknowledged as a master of the older styles as well. He took an opportunistic approach to styles, techniques, and forms, using anything to project human emotion in his music. His dramatic power was such that his surviving operas are again almost repertory staples.

Further listening:

L’Orfeo (opera, 1607)Rogers, London Baroque, Medlam (EMI)

Madrigals of Love and War (1638)Concerto Italiano, Alessandrini (Opus 111)